Practice of Form

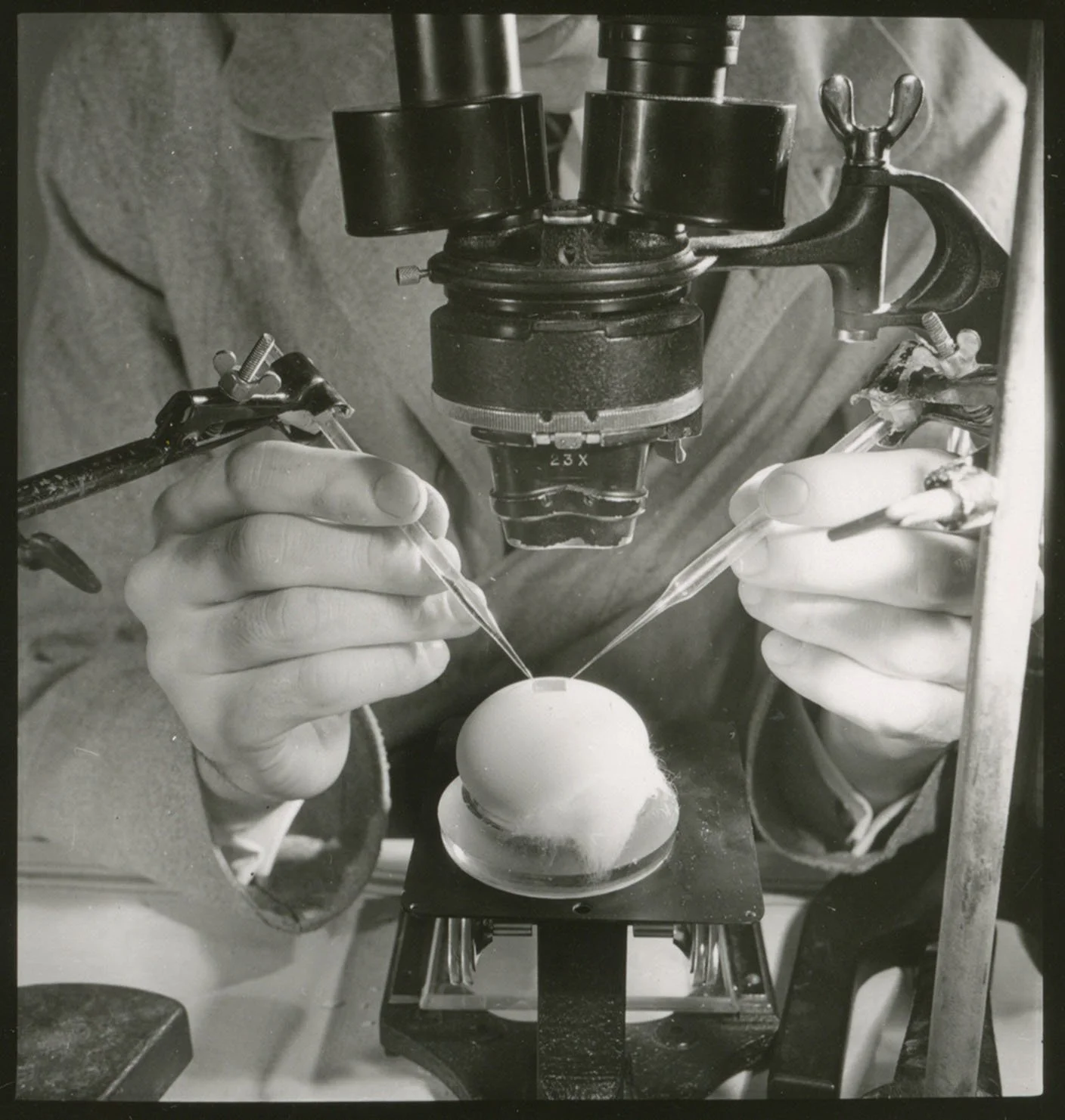

Reconconstructing a cellular slime mold fruiting body from John Tyler Bonner’s microscope slides

Art and science are both practices of observation that share a common visual history. Practice of Form, an exhibit and book project, demonstrates the foundational role of visual making and thinking in the history of developmental biology. Centering multimedia and embodied historiography, Practice of Form proposes research-based artistic practice as a means of crafting feminist histories of science.

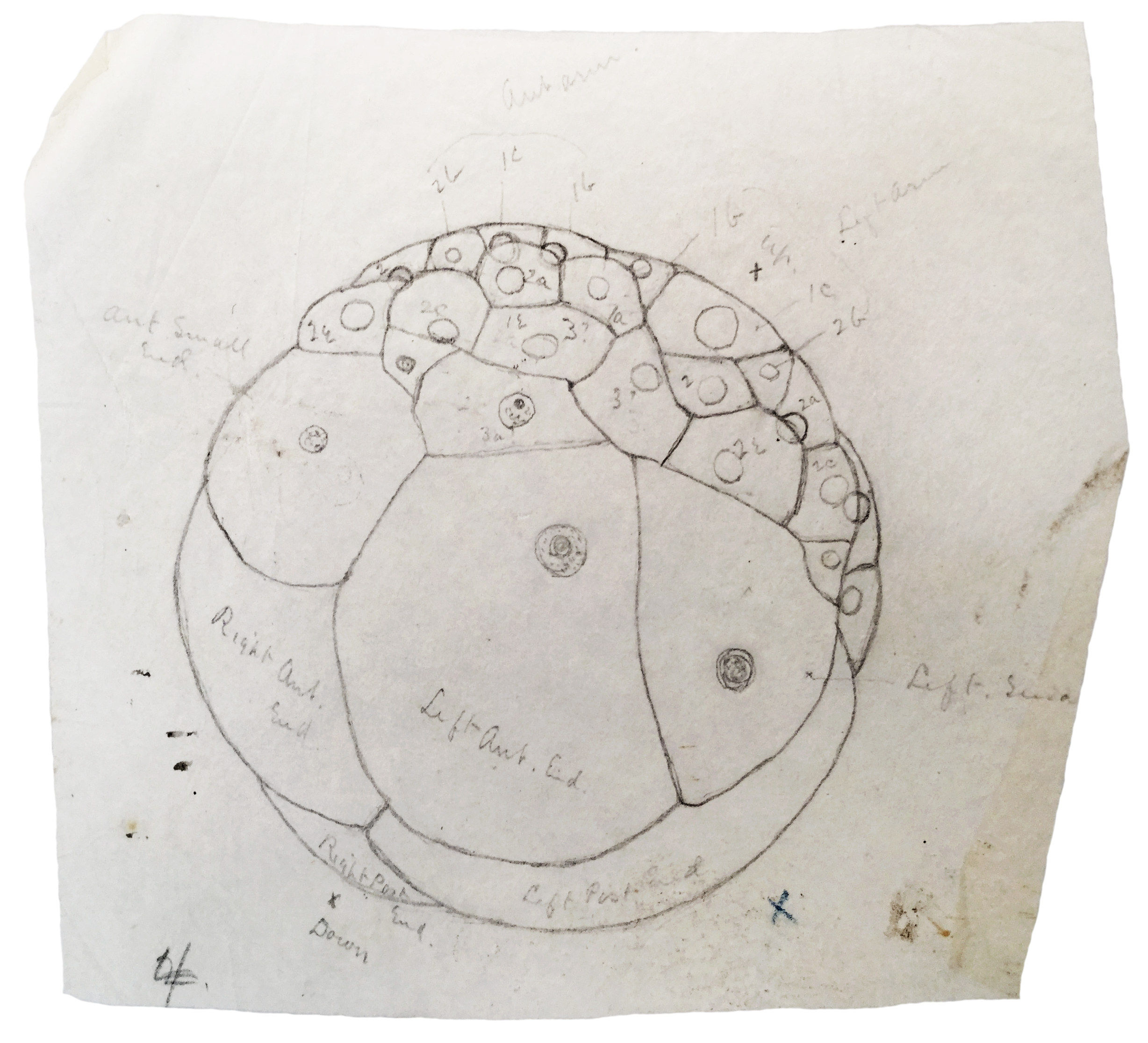

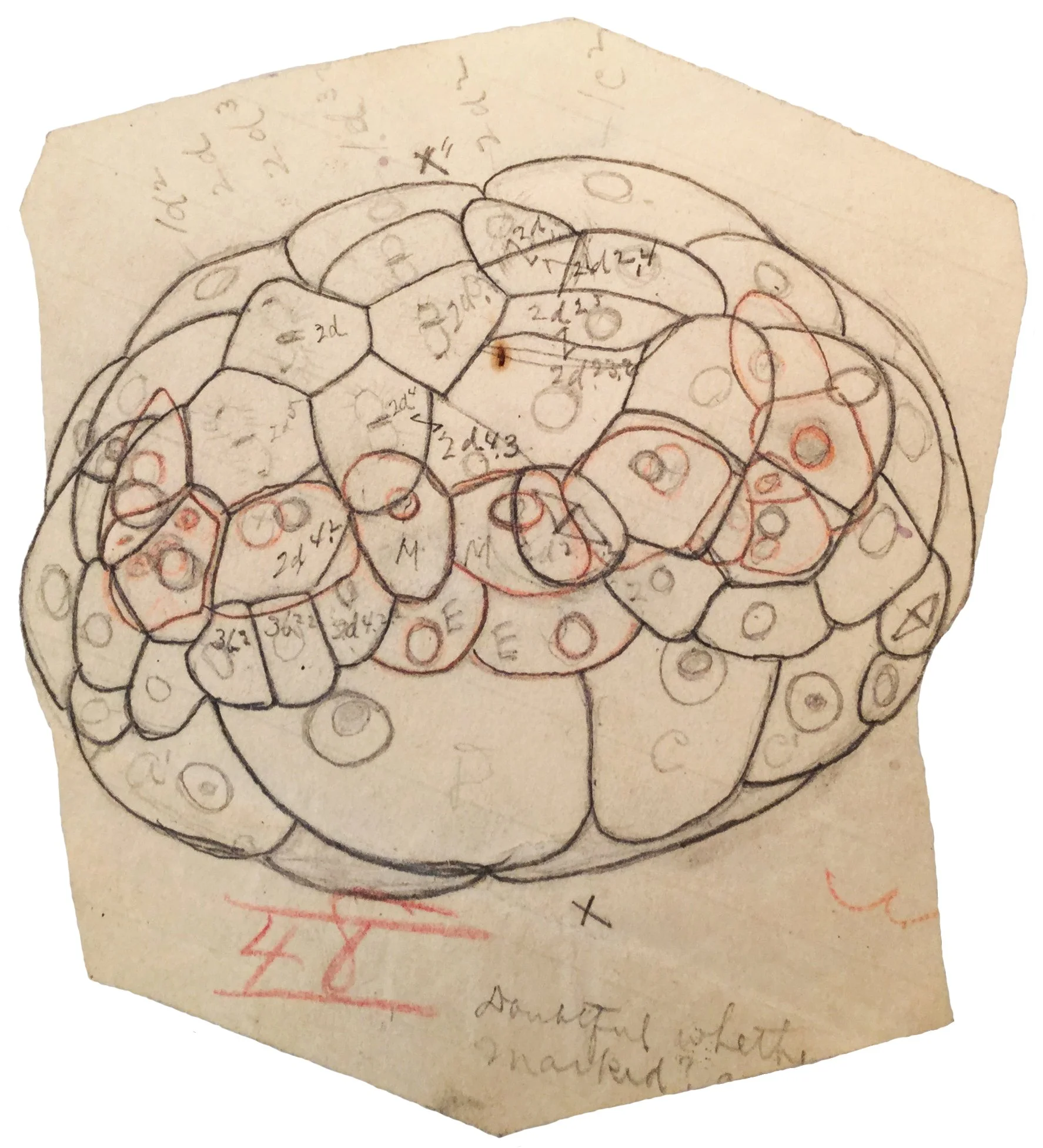

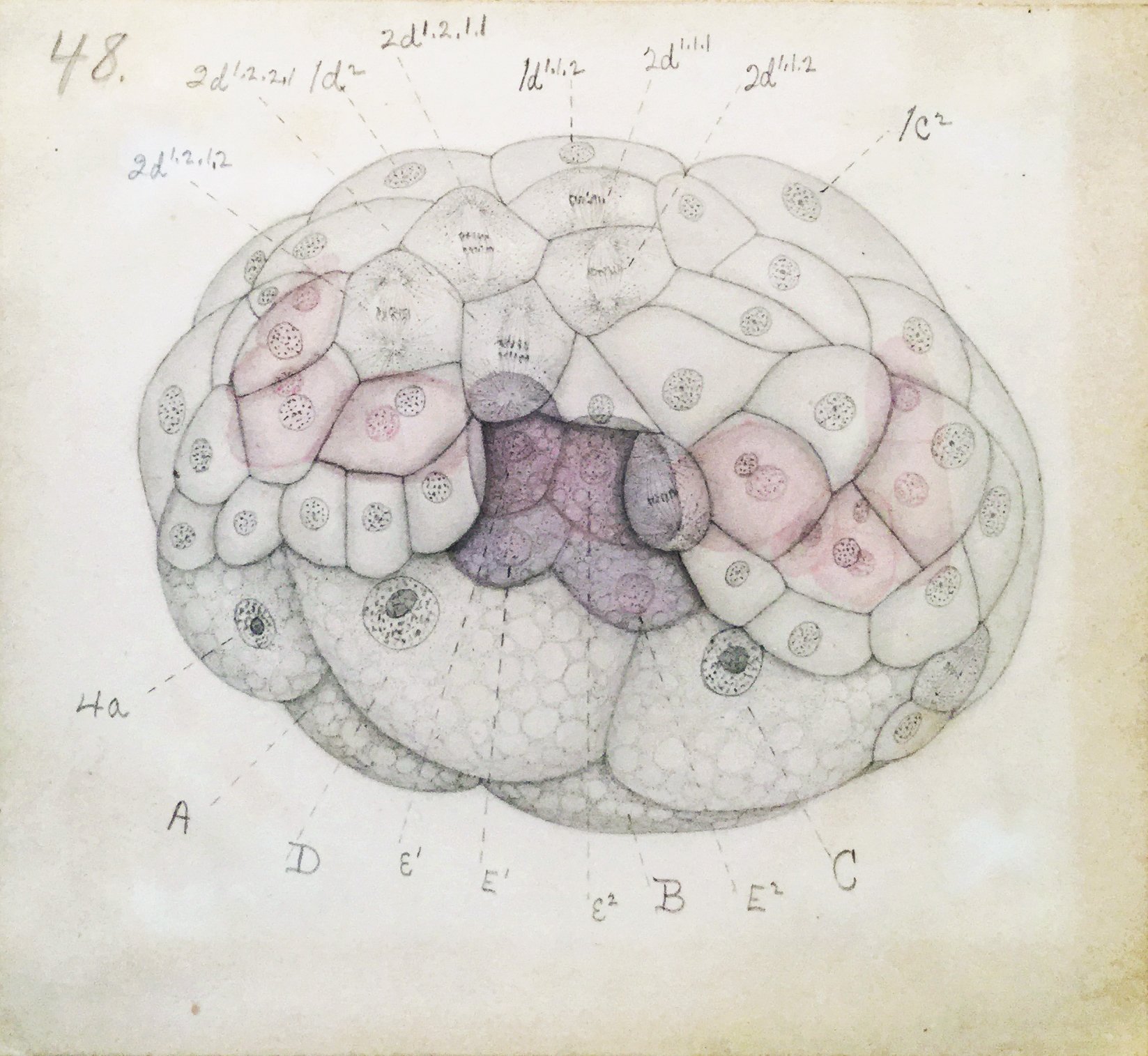

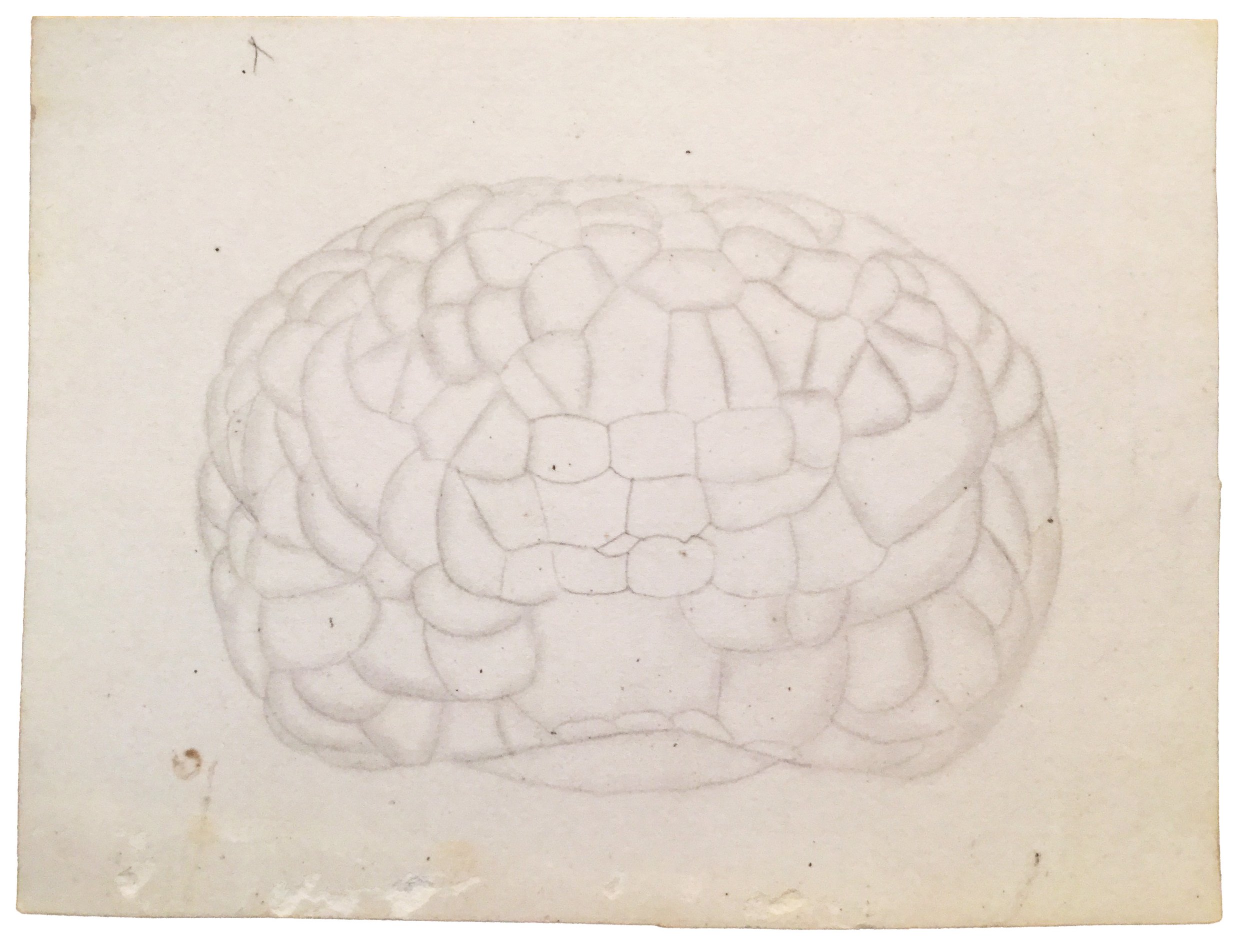

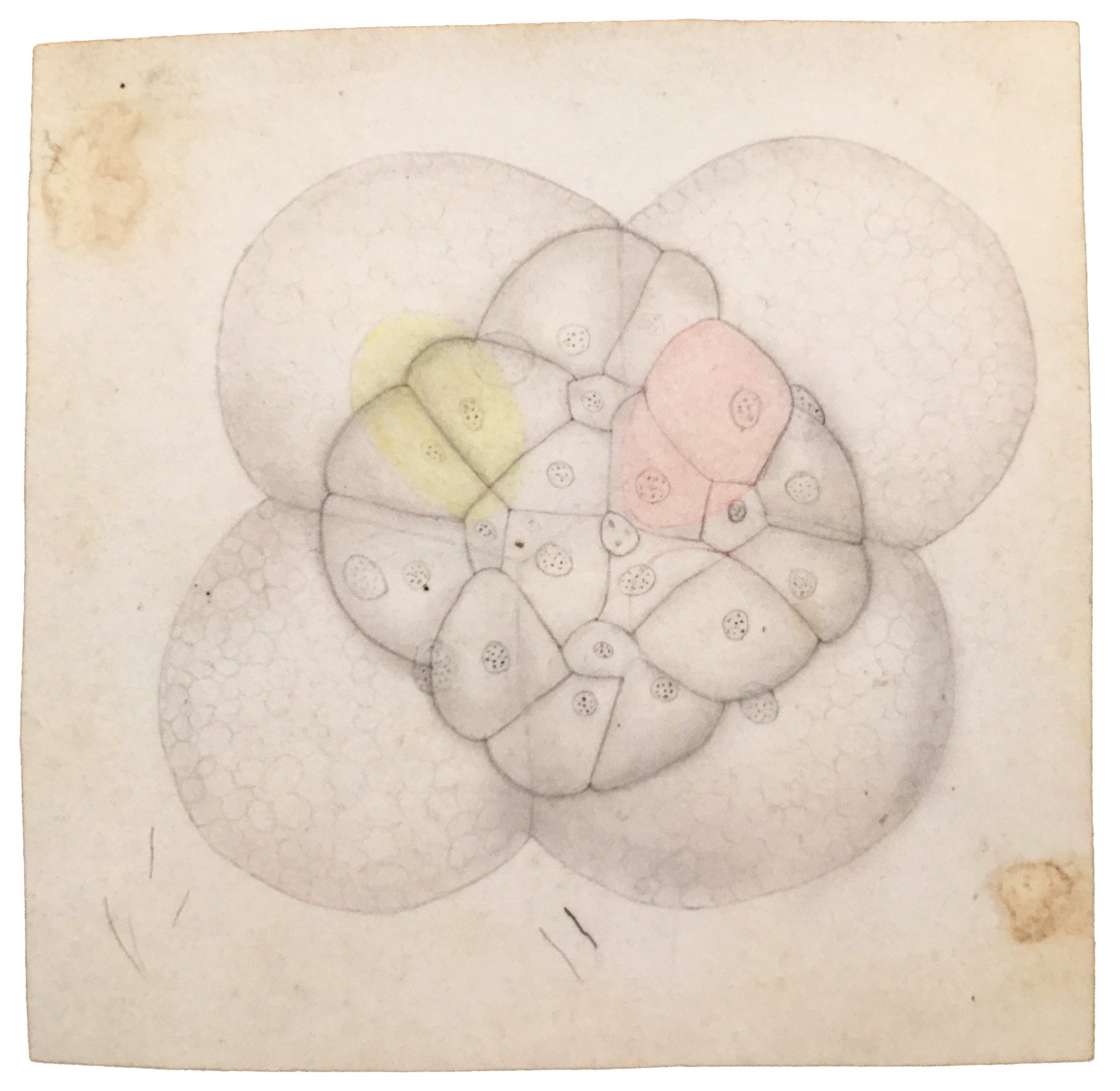

Drawings for The Embryology of Crepidula (E.G. Conklin, c. 1890s)

The first rigorous studies of development at the cellular level emerged in the last decades of the 19th century. Understanding the changing relationships of cells in an embryo required unprecedented attention to embryonic form and its fluctuations through time. Through a reconstruction of Edwin Grant Conklin’s 1890s cell lineage study in snail embryos, one of many carried out during this period, I discovered that the iterative practice of drawing fixed-in-time embryos with a camera lucida produces an embodied animation of development, which is what allowed Conklin to trace cell lineages. Conklin’s drawings, I argue, were no less animated than the first projected microscope films created a decade or more later.

The Embryology of Crepidula, Plate VII (E.G. Conklin, 1897)

By the 1930s, developmental biology had an even wider set of visual tools and approaches to studying organic form, many of which were also central to modern sculpture of the period, as exemplified by the work of Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. Primarily through the work of three biologists–John Tyler Bonner, Johannes Holtfreter, and John Saunders–new theories of morphogenesis, the process of physically shaping an organism, emerged from drawing, filming, photographing, and 3D-modeling slime molds, amphibian embryos, and chicken embryos in the 1940s-60s.

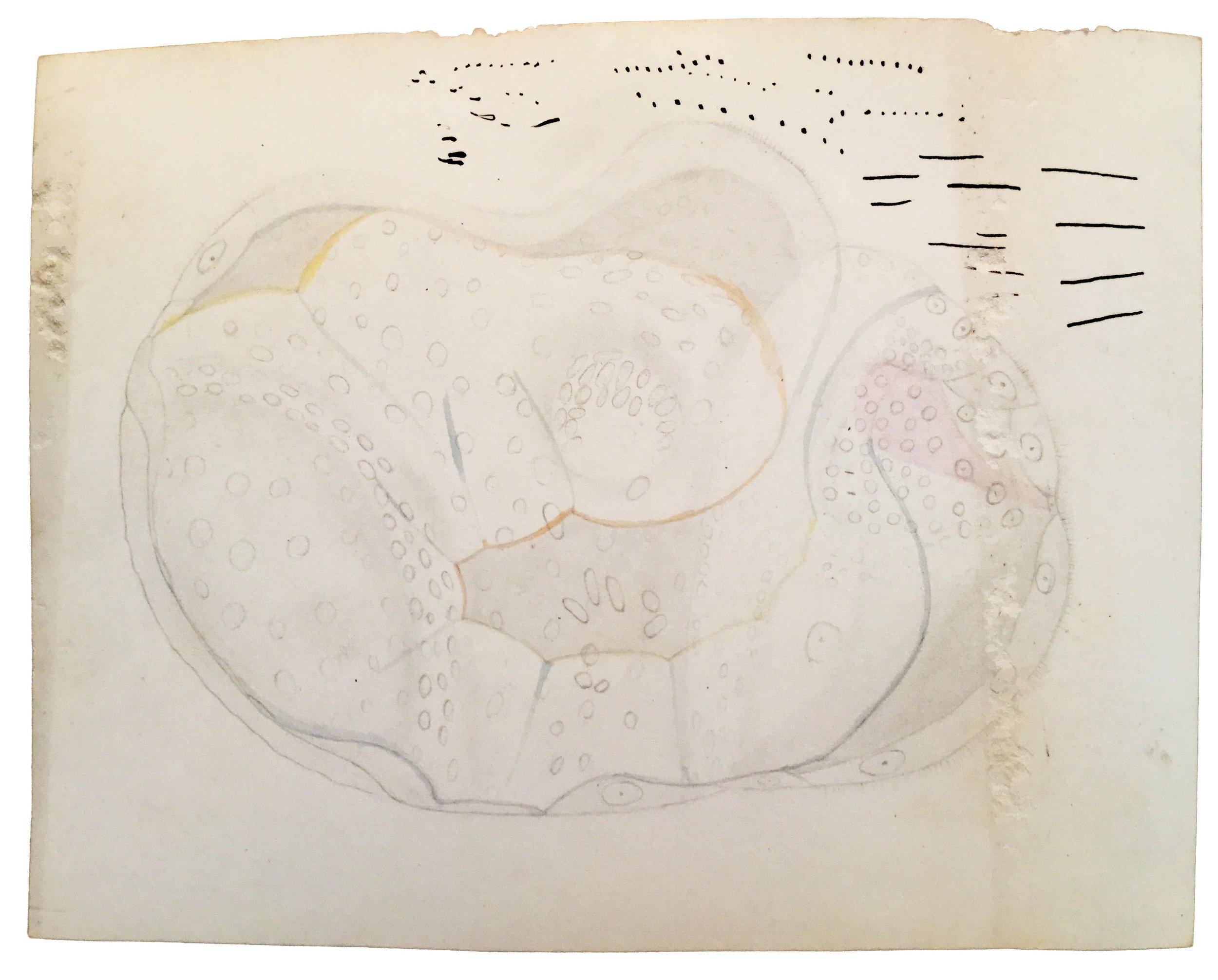

Johannes Holtfreter’s notes on amphibian embryo gastrulation (c. 1942)

John Tyler Bonner’s cellular slime mold microscope slides (c. 1942)

These researchers visualized how, like human-made forms, the bodies of multicellular organisms are sculpted through the addition (cell division), removal (cell death), and manipulation (cell shape change), of cell-material. Documentation of my own practice reconstructing and observing these studies will be integrated with archival materials in the Practice of Form exhibit.

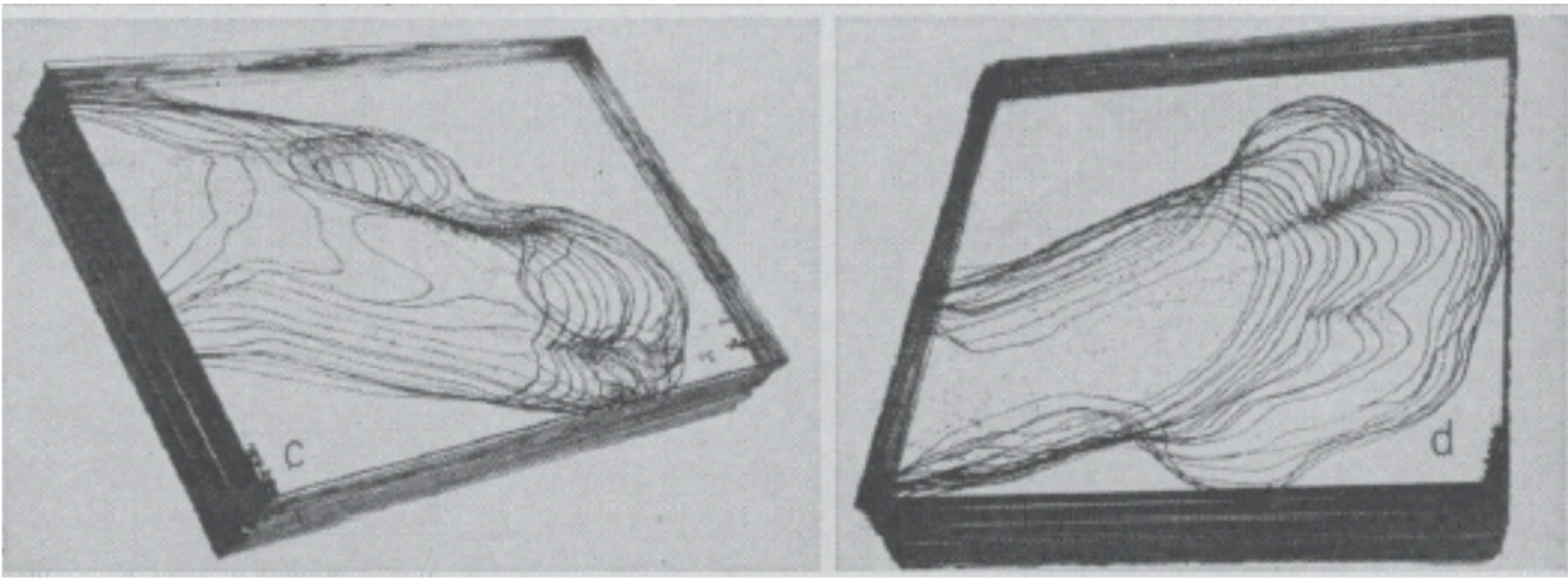

John Saunder’s 3D models of morphogenetic cell death carving embryonic chick wings (c. 1950s)

Chick embryo dissection (c. 1950s)

Archival research in the John Tyler Bonner papers (American Philosophical Society)